By Dr. Tim Orr

Church buildings shape far more than traffic flow and seating arrangements—they shape souls. Before a word is spoken or a song is sung, the space itself has already spoken. It whispers what we believe about God, people, and the gospel. Yet in many churches today, the architecture tells a story of utility rather than theology. This article calls to recover something ancient and often overlooked: the spiritual language of design, where form becomes faith and structure becomes a sacred witness.

A Crisis of Function Without Form

I’ve served on church building campaigns with a price exceeding a million dollars. I remember one project where we spent months discussing where to place classrooms, how to route people efficiently from parking lots to pews, and what kind of flooring would hold up best to kids and coffee spills. The meetings were thoughtful, the intentions noble, and the solutions practical. But what stood out, even then, was that no one asked what kind of spiritual experience the building itself might cultivate. We had blueprints and budgets, but no theology of space. The conversations were responsible for stewarding the congregation’s resources, anticipating growth, addressing accessibility, and efficiency. Everyone involved worked hard and meant well. We talked square footage, cost per seat, and whether the HVAC could handle the summer load. But I noticed something quietly missing: we rarely asked what the building meant spiritually.

We were solving practical problems, but what if our buildings are meant to do more than solve? What if they are intended to stir the imagination, invite awe, and communicate the gospel even before the first word is preached? What if architecture could become a form of liturgy—a spatial catechism that teaches us who God is and who we are about Him? Perhaps our buildings should accommodate ministry, cultivate worship, form spiritual habits, and foster a sense of sacred belonging. That possibility changes everything about how we approach design. What if the architecture of a church doesn’t just house ministry, but forms the people who enter it? That idea haunted me long after the drywall was up and the carpet was laid. We assumed that what happened inside the building mattered—the preaching, the worship, the programs. But what if the building already preaches a message when people walk in, or before?

A Sacred Witness in Stone

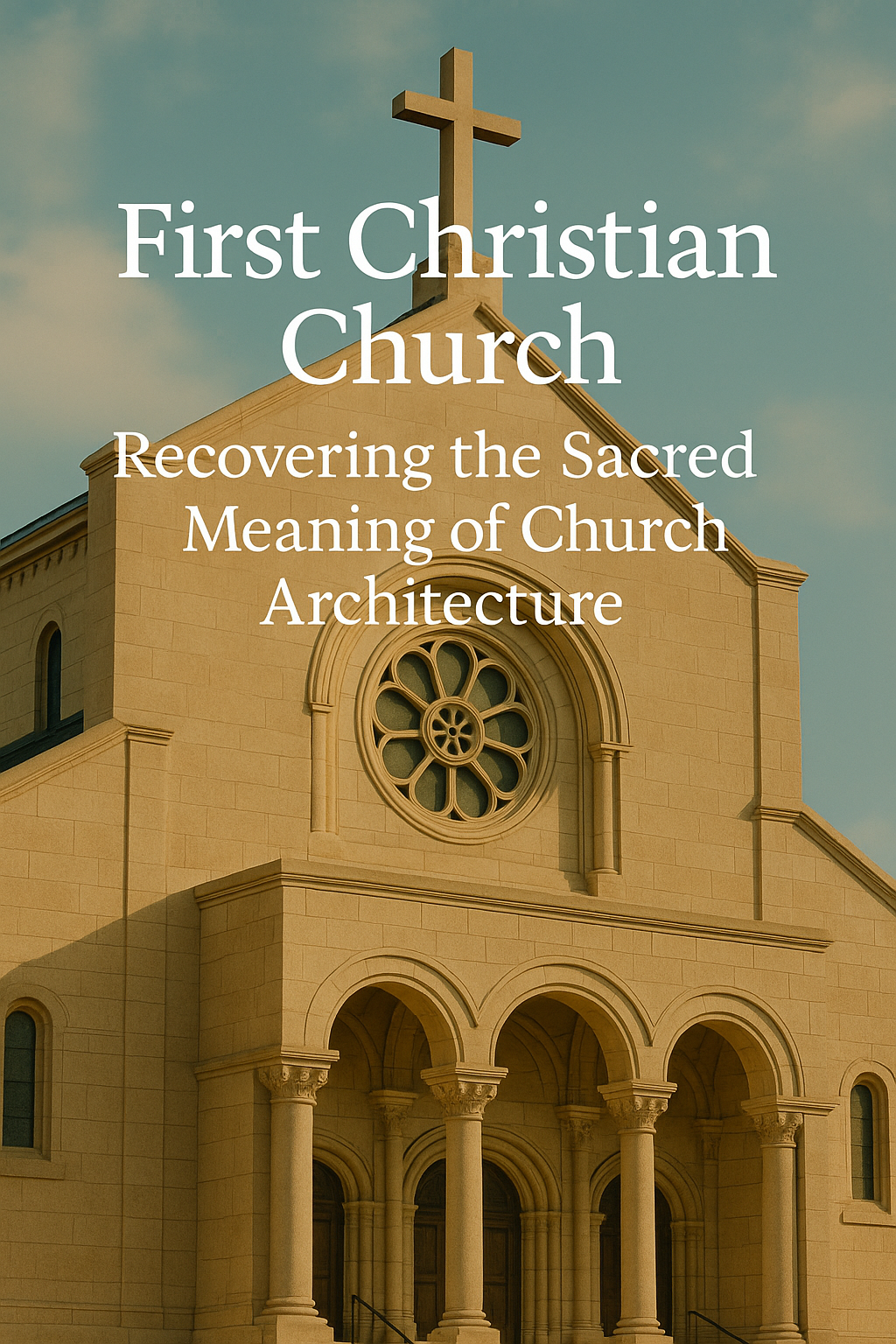

This longing for something more—community and something sacred—drew me to the First Christian Church in Columbus, Indiana. Designed by Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen in 1942, it didn’t just respond to spatial needs; it emerged from a theological vision. The church wasn’t designed as a container for worship; it was shaped to be part of worship. The architecture was a confession of faith, from the layout to the materials to the light. It remains one of the clearest examples of how Christian architecture can tell the gospel's truth without using a single word.

Take, for instance, the entrance. Saarinen intentionally placed it at ground level, with no steps to ascend. This design choice not only embodies humility but visually echoes the core truth of the Incarnation—that God stooped low to meet humanity where we are. In this way, the physical act of entering the church becomes a quiet participation in the theological reality that Christ meets us in our lowliness. The architecture doesn't just invite people in; it enacts the very movement of grace. At first glance, this might appear like a minor design decision related to accessibility or terrain. But it wasn’t. It was a theological statement: no spiritual castes exist in the kingdom of God. Everyone who enters comes on level ground—sinners saved by grace, equally needy, equally welcome.

This speaks powerfully to a world conditioned to wealth, power, race, and status hierarchies. In many traditional church buildings, ascending steps before entering a sanctuary can subtly communicate the elevation of the priest, the institution, or even God’s inaccessibility. But here, the ground-level entrance confronts our craving for spiritual rank. It says: You don’t rise to meet God; God came down to meet you. The church itself becomes a parable of the Incarnation.

Then there’s the 166-foot freestanding campanile, or bell tower. Unlike the vertical steeples of European churches that dominate the skyline as if to assert ecclesial authority, this tower is set apart, inviting, not imposing. It is lofty, yes, but it doesn't loom. The separation between the sanctuary and the tower forms a spatial pause—a gap for reflection. It tells the passerby that faith involves silence, distance, and reverence. You don’t just walk into the holy; you prepare for it.

A reflecting pool sat between the tower and the sanctuary at one time, now removed, but spiritually significant. Its placement invited people to reflect literally and metaphorically on their souls before stepping into worship. Water in the Christian imagination isn’t just aesthetic; it’s covenantal. From the waters of creation to the Red Sea, from the Jordan River to baptismal fonts, water is where God separates chaos from order and brings forth new life. The reflecting pool quietly preached a preparation, cleansing, and rebirth theology. It reminded worshipers that worship doesn’t begin at the first chord of a song, but in the humility of self-examination.

Subtle Design, Spiritual Depth

Inside, the sanctuary does not attempt to dazzle through spectacle. Unlike many contemporary worship environments that rely on dramatic lighting, oversized screens, or elaborate staging to evoke emotion, Saarinen's design invites something subtler. No distractions are vying for your attention—no spectacle competing with the sacred. Instead, the simplicity becomes a spiritual guide, encouraging inward stillness and reverence. The sanctuary gently reminds us that awe doesn't require amplification—only authenticity and space to behold the presence of God. There are no golden altars, no gothic arches, no stained-glass stories. And yet, it is not empty. It is full of intentional restraint—designed to silence the world's noise and draw the soul inward. Natural light does what no spotlight can do: it sanctifies space through subtlety. The room’s simple geometry speaks of the order of creation, and the absence of symbols creates room for the sacred, rather than cluttering it with religious busyness.

Saarinen’s restraint feels like an architectural embodiment of the desert fathers—those early Christians who fled to the wilderness not to escape the world, but to see God more clearly. This is not minimalism for minimalism’s sake. It is clarity for communion’s sake. In a culture of distraction, the space offers permission to breathe, to pause, to pray. It is architecture designed for encounter, not performance.

Everyday Spaces, Eternal Purpose

The church's layout also challenges a sacred-secular divide. Saarinen did not hide the community spaces—classrooms, offices, fellowship areas—they were integrated into the building’s flow. That was deliberate. It tells us that discipleship is not limited to the sanctuary. Learning, serving, organizing, and eating together are not peripheral to worship; they are worship. The building resists compartmentalization and insists that all of life belongs to God.

Even more radical is the theological openness embedded in the architecture. No denominational emblems or stained-glass scenes are tied to a single tradition. The congregation commissioned the building, believing Christian unity should be reflected in Christian space. They didn’t want to build a fortress of sectarian identity. They wanted a place where the weary could rest and the curious could come without intimidation. The building echoes Christ’s invitation: “Come to Me, all who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.”

That kind of spiritual hospitality is rare today—many churches unintentionally design spaces that speak insider language before a single word is spoken. Through visual symbols or architectural styles, buildings can quickly signal who belongs and who doesn’t. However, the First Christian Church in Columbus was modeled in another way. It says, without words, you are welcome here because God is. No explanation is needed.

Over the years, I’ve walked into newly built churches that were state-of-the-art, climate-controlled, acoustically tuned, and tech-savvy. But sometimes, they lacked a soul. The spaces were optimized for performance, not presence. The foyers were expansive, but spiritually thin. The sanctuaries were sleek, but they didn’t feel sacred. And I couldn’t help but wonder: what story is this building telling?

Buildings shape people, whether we intend them to or not. This theme runs through everything I’ve shared—from the ground-level entrance that models incarnational grace to the light-filled sanctuary that cultivates awe. Even the bell tower's spatial separation, or the reflecting pool's theological silence, plays a formative role. These aren't just design choices—they are spiritual educators, quietly shaping how we see God, ourselves, and one another. It’s a truth worth naming repeatedly: our spaces disciple us. A church that looks like a shopping mall teaches us to consume faith. A sanctuary designed like a theater trains us to spectate. But a church like First Christian in Columbus invites us to dwell—to be quiet, small, open to mystery. That kind of space doesn’t just serve ministry—it becomes ministry.

First Christian Church shows us what’s possible when form and faith are allowed to dance together. It reminds us that architecture is not neutral. Every line, every entryway, every shaft of light carries a message. And when those messages are aligned with the gospel, a building becomes more than a space. It becomes a witness.

Who is Dr. Tim Orr?

Tim serves full-time with Crescent Project as the assistant director of the internship program and area coordinator, where he is also deeply involved in outreach across the UK. A scholar of Islam, Evangelical minister, conference speaker, and interfaith consultant, Tim brings over 30 years of experience in cross-cultural ministry. He holds six academic degrees, including a Doctor of Ministry from Liberty University and a Master’s in Islamic Studies from the Islamic College in London.

In addition to his ministry work, Tim is a research associate with the Congregations and Polarization Project at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at Indiana University Indianapolis. His research interests include Islamic antisemitism, American Evangelicalism, and Islamic feminism. He has spoken at leading universities and mosques throughout the UK—including Oxford University, Imperial College London, and the University of Tehran—and has published widely in peer-reviewed Islamic academic journals. Tim is also the author of four books.