When I studied for my MA in Islamic Studies at the Islamic College in London, I was given the opportunity to learn about Shia Islam from within, not through the filter of Western headlines or ideological caricatures, but through rigorous academic engagement. The college was not hardline, nor was it interested in grooming political operatives. It was a place of learning, characterized by careful scholarship, where professors encouraged students to think critically and engage respectfully.

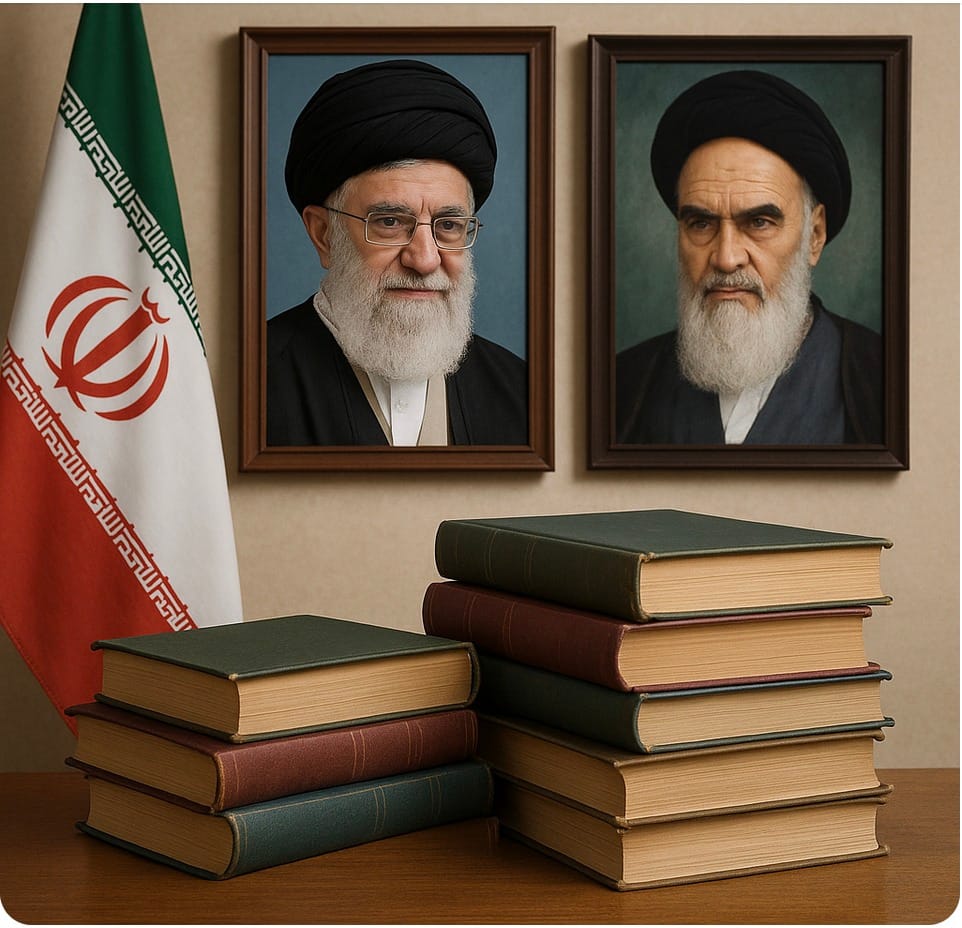

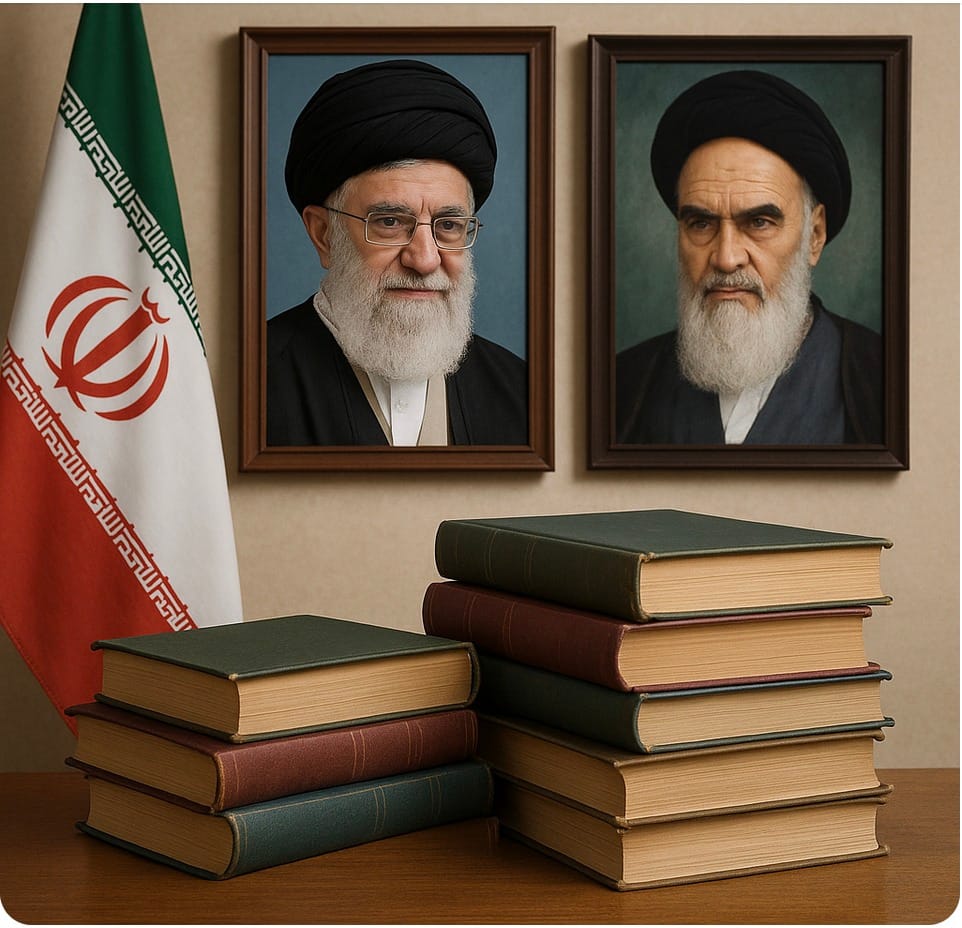

Yet through the texts I read, especially those authored by clerics who shaped Iran’s modern identity, I began to grasp just how deeply theology and politics are fused in the Islamic Republic. In particular, the concept of Wilayat al-Faqih, or Guardianship of the Jurist, stood out as central. Ayatollah Khomeini argued that in the Mahdi’s absence, a qualified jurist should rule the Islamic community. That may sound reasonable within a religious framework, but the consequences of this doctrine have been disastrous. It effectively turns the Supreme Leader into a divine deputy, granting him not only political control but also religious infallibility. That is not just dangerous, it is theocratic absolutism dressed up in sacred language.

The regime in Iran has taken this idea and run with it, creating a system where dissent becomes heresy and where one man claims to speak on behalf of a hidden, infallible messianic figure. I saw how this unfolded through the writings I studied, not in abstract theory, but in the lived theology of a state that views itself as ordained to rule in the Mahdi’s absence. What is more alarming is that some clerics, particularly hardliners, believe that chaos and conflict can help usher in the Mahdi’s return. That kind of thinking is not just fringe, it has implications for Iran’s foreign policy. It helps explain the regime’s militant posture toward Israel, its persistent support for destabilizing proxy wars, and its willingness to tolerate unimaginable economic suffering at home. As one analyst put it, “Iran doesn’t just endure crisis, it needs it.” When I read that, I remembered the texts I encountered in my coursework that seemed to blur the line between divine preparation and calculated political unrest. It gave me a deeper understanding of how apocalyptic thinking is not just present in the regime’s worldview, it is part of the machinery.

One area where this theology becomes particularly toxic is in Iran’s obsession with Israel. On the surface, their hostility may seem like typical geopolitical tension, but it runs much deeper than that. In Shia eschatology, which I explored through classical and modern texts, Israel is often portrayed as a symbol of corruption and injustice in the end times. Some traditions suggest that the Mahdi will liberate Jerusalem, making it a central arena in the apocalyptic drama. That makes Iran’s anti-Zionism more than just political, it is cosmic. I never heard this explicitly preached in my courses, but it was clear in the literature. This is not about the two-state solution. It is about a theological script in which Israel’s destruction becomes a necessary step toward redemption. When leaders like Khamenei couch their hatred of Israel in religious terms, they are not being metaphorical. They are positioning themselves as actors in a divine narrative, and that narrative leaves no room for coexistence or compromise.

The regime’s use of martyrdom fits this pattern as well. I studied the deep significance of Karbala in Shia thought, and I came to appreciate how the memory of Husayn’s sacrifice has shaped centuries of devotion, grief, and moral resolve. But Iran has politicized that tradition. Figures like Qassem Soleimani are not just eulogized as patriots, they are sanctified as martyrs in the Mahdi’s struggle. I remember seeing images after Soleimani’s death that portrayed him not just as a fallen commander, but as a saintlike figure bathed in heavenly light, sword in hand, poised to strike down the enemies of Islam. The message was unmistakable: dying in service to the regime’s goals is not just heroic, it is holy. That is the kind of narrative that makes violence sustainable. It elevates warfare into a sacred duty, blurs the lines between faith and fanaticism, and prepares a population to sacrifice themselves not for justice, but for the glory of a regime that claims divine endorsement.

I am deeply critical of this regime, not just because of its human rights abuses or its brutal repression of dissent, but because of how it wraps those abuses in sacred justification. Studying at the Islamic College did not make me sympathetic to this system. Quite the opposite. It gave me the intellectual tools and firsthand exposure to understand it on its own terms, and then to challenge it more effectively. I did not come away impressed by the regime’s theology. I came away alarmed. The Islamic Republic claims to govern in the Mahdi’s absence, but in practice, it governs through coercion, censorship, and calculated eschatology. Its leaders do not just see themselves as administrators, they see themselves as agents of the end times.That belief drives decisions that cost lives, fuel conflict, and suppress truth. And no amount of religious language can disguise that reality.

Who is Dr. Tim Orr?

Tim serves full-time with Crescent Project as the assistant director of the internship program and area coordinator, where he is also deeply involved in outreach across the UK. A scholar of Islam, Evangelical minister, conference speaker, and interfaith consultant, Tim brings over 30 years of experience in cross-cultural ministry. He holds six academic degrees, including a Doctor of Ministry from Liberty University and a Master’s in Islamic Studies from the Islamic College in London.

In addition to his ministry work, Tim is a research associate with the Congregations and Polarization Project at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at Indiana University Indianapolis. His research interests include Islamic antisemitism, American Evangelicalism, and Islamic feminism. He has spoken at leading universities and mosques throughout the UK, including Oxford University, Imperial College London, and the University of Tehran. He has published in peer-reviewed Islamic academic journals. Tim is also the author of four books.